Section 1: Facial Architecture & Structural Reading

Definition

Facial architecture refers to the integrated system of bone structure, muscle attachments, fat pad distribution, and skin quality that determines the three-dimensional topography of the face. Structural reading is the analytical practice of decoding this architecture to identify the constraints and opportunities it presents for brow design.

At the mastery level, structural reading becomes the foundation upon which all subsequent decisions rest.

The face is not a flat canvas awaiting decoration; it is a dimensional structure with slopes, prominences, concavities, and transition zones. Brow design that ignores this dimensionality produces results that appear superimposed rather than integrated. The master practitioner reads structure before considering shape, understanding that optimal brow architecture must honour the face it inhabits.

Theory

Facial architecture theory begins with recognition that every face represents a unique configuration of inherited skeletal structure, developmental influences, aging processes, and environmental factors. While certain patterns recur across populations, no two faces present identical architectural profiles. This individuality demands analytical approaches that detect specific configurations rather than apply categorical assumptions.

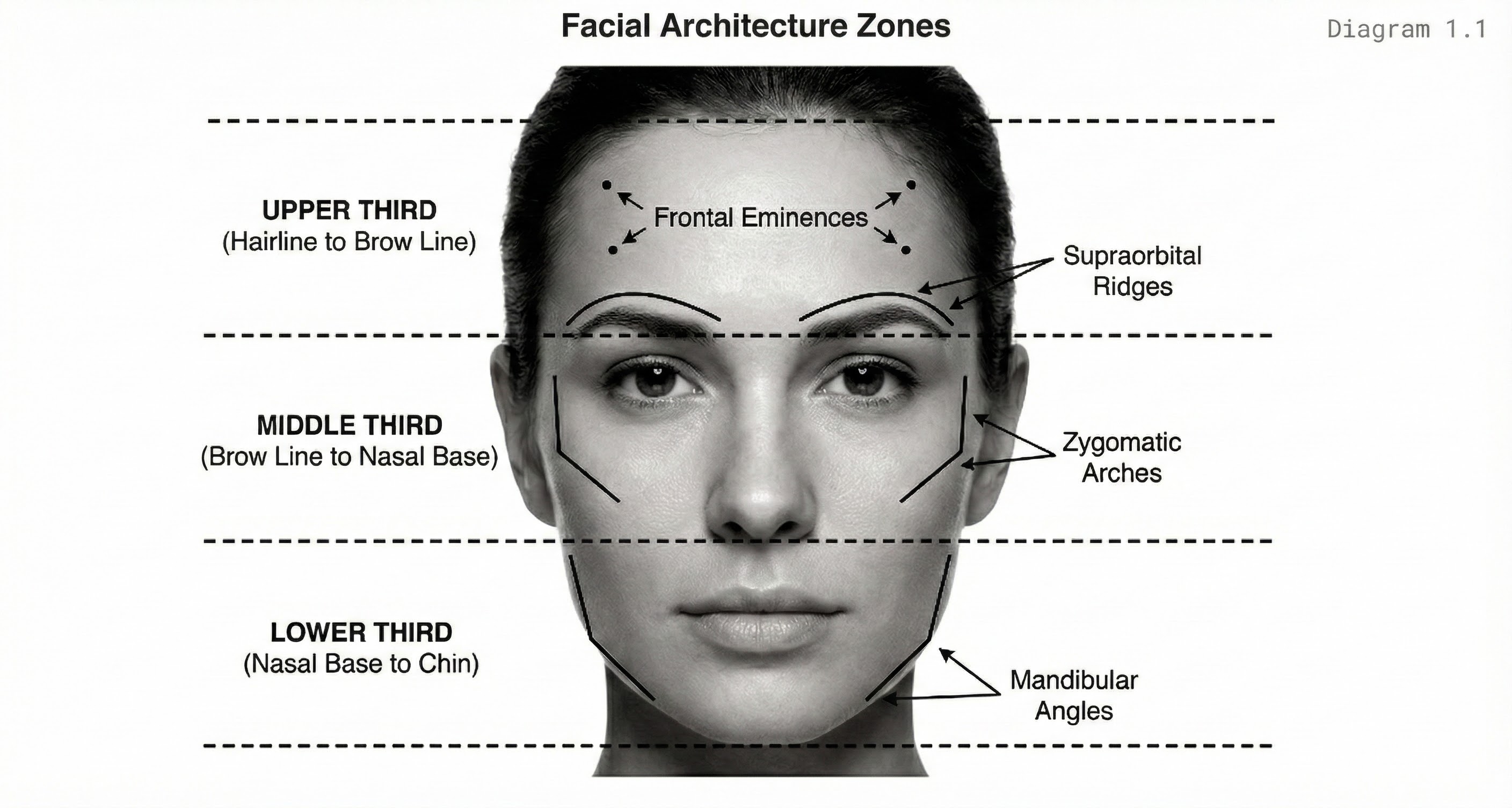

The Three Facial Zones

The face divides into structural zones with distinct characteristics:

Upper Third: Encompasses forehead and brow region, dominated by the frontal bone and its interaction with the orbital structures.

Middle Third: Involves the complex geometry of nasal bones, zygomatic arches, and maxillary prominences.

Lower Third: Reflects mandibular structure and dental occlusion.

Brow design primarily engages the upper third while remaining influenced by the proportional relationships established across all three zones.

Facial Architecture Zones

Purpose: Establish the three-zone facial division with skeletal landmarks

A frontal view of a gender-neutral face divided into horizontal thirds by dashed lines. The upper third spans from hairline to brow line, the middle third from brow line to nasal base, the lower third from nasal base to chin. Key skeletal landmarks are indicated: frontal eminences as paired dots on the upper third, supraorbital ridges as curved lines following the brow bone, zygomatic arches at the lateral edges of the middle third.

The Primacy of Skeletal Landmarks

Structural reading theory emphasises the primacy of skeletal landmarks over soft tissue appearances. Soft tissue (muscle, fat, and skin) overlays skeletal structure and can obscure or modify its apparent configuration. However, skeletal structure determines the fundamental geometry within which soft tissue operates.

The master practitioner reads through soft tissue to the bone beneath, recognising that what appears on the surface may not accurately represent underlying architecture.

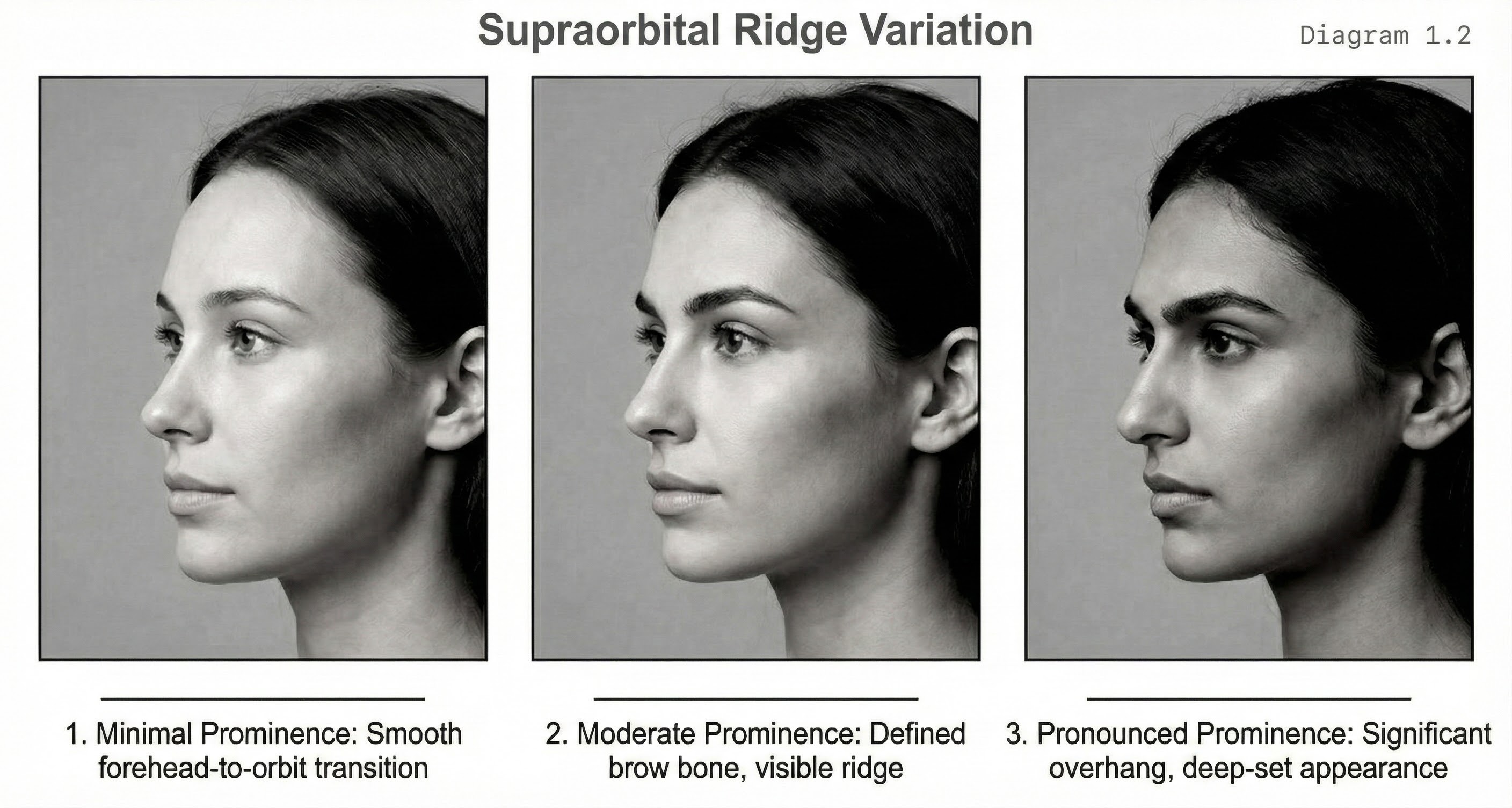

The Transitional Zone

The brow itself occupies a transitional zone between the flat expanse of the forehead and the recessed volume of the orbital cavity. This transition involves the supraorbital ridge, a thickening of the frontal bone that creates the shelf upon which the brow sits.

Ridge prominence varies considerably across individuals, from nearly flat configurations to pronounced overhangs. This variation profoundly influences how brows appear and how they should be designed.

Supraorbital Ridge Variation

Purpose: Illustrate the range of ridge prominence across individuals

Three profile silhouettes showing variation in supraorbital ridge prominence. The first shows minimal prominence with a smooth forehead-to-orbit transition. The second shows moderate prominence with visible ridge creating defined brow bone. The third shows pronounced prominence with significant overhang above the orbital cavity.

Methodology

Structural reading methodology proceeds through systematic assessment of anatomical landmarks, proportional relationships, and dimensional characteristics. The process begins with global observation (the overall impression of facial configuration) before proceeding to zone-specific analysis and landmark identification.

Global Assessment

Evaluates facial proportions in relation to classical ideals while recognising that deviation from ideals does not constitute deficiency. The practitioner notes whether the face reads as long or short, narrow or wide, angular or rounded. These global impressions establish context for subsequent detailed analysis.

Zone Assessment

Examines each facial third independently, noting characteristics that influence brow design. In the upper third, forehead height, slope, and convexity are documented. Hairline position and shape provide upper boundary context. Temporal regions are assessed for width and hollowing. The relationship between forehead and orbital zones receives particular attention.

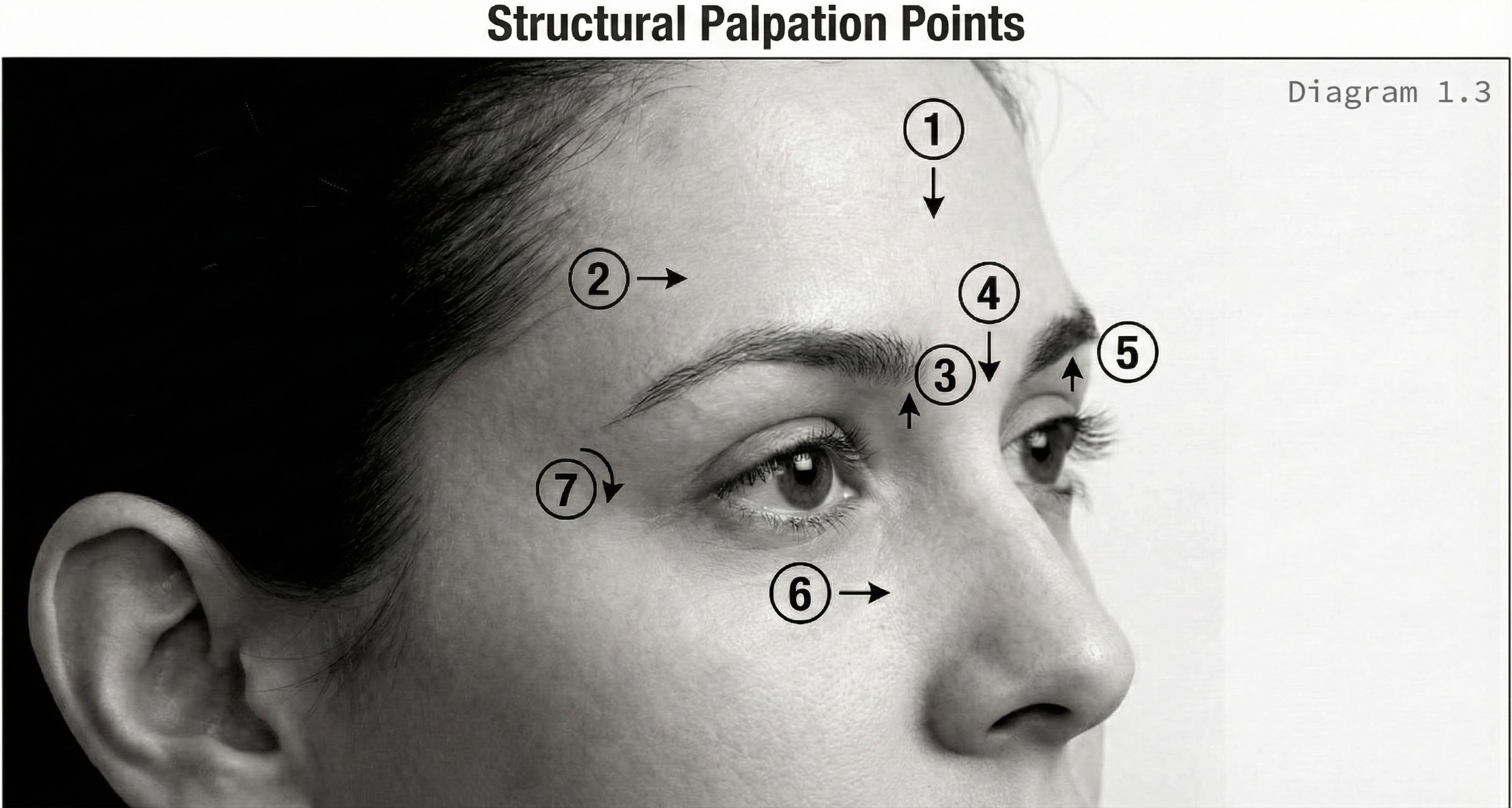

Landmark Identification

Proceeds systematically through structures relevant to brow positioning:

- The supraorbital ridge is palpated and its prominence characterised

- Orbital rim contour is traced, noting variations in depth and shape

- The frontal eminences (paired prominences on either side of the forehead midline) are identified

- Temporal ridges marking the lateral boundaries of the forehead are located

Structural Palpation Points

Purpose: Guide systematic palpation assessment

A three-quarter view face with numbered circles indicating key palpation locations: (1) frontal eminence, (2) temporal ridge, (3) supraorbital ridge medial, (4) supraorbital ridge apex, (5) supraorbital ridge lateral, (6) orbital rim, (7) temporal fossa. Arrows indicate palpation direction for each point.

Dimensional Assessment

Involves measurement and proportion analysis:

- Vertical measurements establish relationships between hairline, brow, and eye positions

- Horizontal measurements document eye spacing, temple width, and facial width at various levels

- The practitioner develops proportional ratios that characterise the individual face

Techniques

Palpation Technique

Provides access to skeletal structure obscured by soft tissue. The practitioner uses gentle but firm finger pressure to identify bone landmarks beneath skin and subcutaneous tissue.

- The supraorbital ridge is palpated from medial to lateral, noting prominence variation along its length

- Orbital rim contour is traced to identify asymmetries invisible on surface examination

- Temporal hollowing is assessed through palpation of the temporal fossa

Visual Analysis Technique

Employs systematic observation under controlled lighting conditions.

- Direct frontal lighting reveals symmetry and proportion but obscures dimensionality

- Angled lighting creates shadows that reveal topography: prominences cast shadows while concavities fall into shadow

- The practitioner observes the face under varied lighting to build complete dimensional understanding

Photographic Analysis

Provides documentation and facilitates proportional measurement.

- Standardised positioning (front facing, profile, and three-quarter views) creates comparable images

- Grid overlay assists proportion analysis

- Before-and-after comparison requires consistent photographic protocols

Dynamic Assessment Technique

Evaluates how structure behaves during expression.

The client is directed through a sequence of expressions (brow raise, frown, squint, smile) while the practitioner observes structural response. Skin mobility, muscle recruitment patterns, and asymmetric behaviour become apparent through dynamic observation that static assessment cannot reveal.

Professional Notes

Structural reading proficiency develops through deliberate practice and accumulating experience. Early practitioners tend toward categorical thinking, classifying faces into types and applying type-appropriate approaches. Mastery involves transcending categories to perceive individual configurations in their unique particularity.

Documentation of structural observations creates reference material that supports both immediate design decisions and longitudinal learning. The practitioner who systematically records structural assessments, correlates them with design choices and outcomes, develops pattern recognition that cannot be taught but only acquired.

Cultural and ethnic considerations influence structural reading interpretation. Skeletal architecture varies systematically across populations, and normative assumptions derived from one population may misread others. The master practitioner develops familiarity with diverse structural presentations while avoiding both stereotype application and difference denial.

Common Mistakes

Soft Tissue Over-Reliance: The most prevalent structural reading error. Practitioners assess what they see rather than what underlies what they see, leading to designs that follow superficial contours rather than skeletal architecture. When soft tissue position shifts (through aging, weight change, or simply gravitational effects over the course of a day), designs based on soft tissue alone lose their relationship to underlying structure.

Categorical Assignment Errors: Occur when practitioners match faces to type categories rather than reading individual configurations. The face that partially resembles a recognised type but deviates in significant particulars receives inappropriate design through categorical assignment. Every face warrants individual assessment regardless of apparent type resemblance.

Symmetry Assumption Errors: Arise from the expectation that faces present bilateral symmetry. Most faces exhibit asymmetry that structural reading must detect and design must address. The practitioner who assumes symmetry without verification will miss asymmetries that subsequently produce asymmetric results.

Lighting Dependency Errors: Result from assessment under only one lighting condition. Structure that appears one way under salon lighting may present differently in natural light or varied artificial conditions.

Expert Insights

The master practitioner develops what might be called structural intuition, the capacity to read architecture immediately upon seeing a face, before conscious analysis begins. This intuition is not mystical; it is the product of accumulated experience that has trained pattern recognition below conscious awareness. However, intuition should inform rather than replace systematic assessment.

Difficult structural readings often involve faces that deviate from familiar patterns. The face with unusual proportions, atypical bone structure, or combinations of features the practitioner has not previously encountered requires careful analytical work.The master approaches these cases with curiosity rather than frustration, recognising that challenging presentations expand professional capability.

Structural reading skill transfers across client populations. The practitioner who can read structure accurately reads it accurately regardless of age, ethnicity, or gender presentation.

Practical Application

In clinical application, structural reading precedes and informs all subsequent consultation phases. Before discussing desired outcomes or presenting design options, the practitioner conducts structural assessment. This assessment identifies what is possible, what is optimal, and what is contraindicated for the specific architecture presented.

Structural findings should be communicated to clients in accessible terms. The client benefits from understanding why certain designs suit their architecture while others would not. This communication builds trust, manages expectations, and supports informed consent.

Documentation of structural findings creates baseline reference for future appointments. As clients age or undergo other changes, comparison to baseline structural documentation supports appropriate design evolution.