Section 3: Muscle Dynamics, Expression & Brow Behaviour

Definition

Muscle dynamics in the brow context refers to the functional behaviour of muscles that attach to, originate from, or influence the position and movement of the brow region. Expression analysis examines how these muscles activate during emotional display and voluntary control.

Brow behaviour assessment integrates muscular and expressive findings to predict how brow design will perform dynamically—not merely how it will appear at rest, but how it will move, shift, and respond to facial animation.

The brow is not a static structure; it is a mobile zone influenced by multiple muscles with sometimes opposing actions. Designs that appear optimal at rest may distort unacceptably during expression. Mastery-level practice requires understanding muscular dynamics sufficiently to predict and accommodate expressive behaviour.

Theory

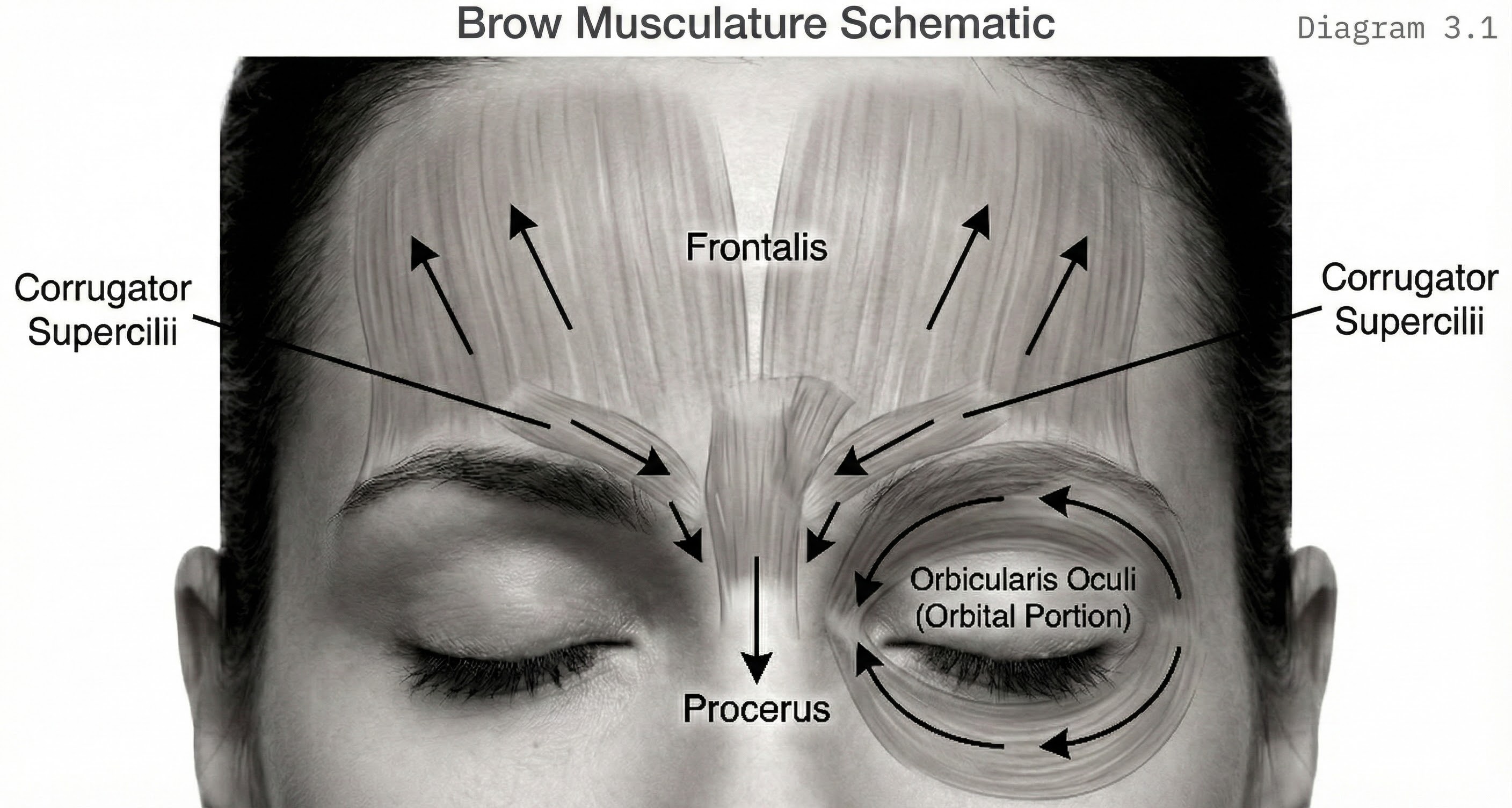

Muscle dynamics theory for the brow begins with understanding the key muscles of the brow complex.

The Frontalis Muscle

The primary brow elevator, the frontalis covers the forehead as a broad sheet inserting into the skin above the brow. When frontalis contracts, it raises the brow and creates horizontal forehead creases. Frontalis action varies considerably across individuals in strength, distribution, and symmetry.

The Procerus Muscle

Lies at the nasal root, attaching from nasal bone to glabellar skin. Procerus contraction pulls the medial brow inferiorly and creates horizontal creases at the nasal root. This muscle contributes to frowning expressions and influences medial brow position during negative emotional display.

The Corrugator Supercilii

Originates from the medial supraorbital ridge and inserts into brow skin above the mid-pupil. Corrugator contraction pulls the brow medially and inferiorly, creating vertical glabellar creases—the so-called frown lines. Corrugator strength varies across individuals and influences how much the medial brow moves during expression.

Brow Musculature Schematic

Purpose: Illustrate the muscles affecting brow position and movement

An anterior view of the forehead and brow region with musculature illustrated in semi-transparent overlay. The frontalis appears as a broad sheet across the forehead with vertical fiber direction. The corrugator supercilii appears as an oblique muscle from medial brow bone to mid-brow skin. The procerus appears as a vertical muscle at the nasal root.

The Orbicularis Oculi

While primarily responsible for eye closure, this muscle influences the inferior brow margin. The upper portion of orbicularis can depress the lateral brow during strong closure or squinting. This creates the effect of brow lowering that accompanies intense emotional expression or bright light response.

The Depressor Supercilii

When present as a distinct muscle rather than part of orbicularis, provides additional medial brow depression. Anatomical variation exists regarding this muscle's presence and definition. Where prominent, it contributes to medial brow movement during negative expression.

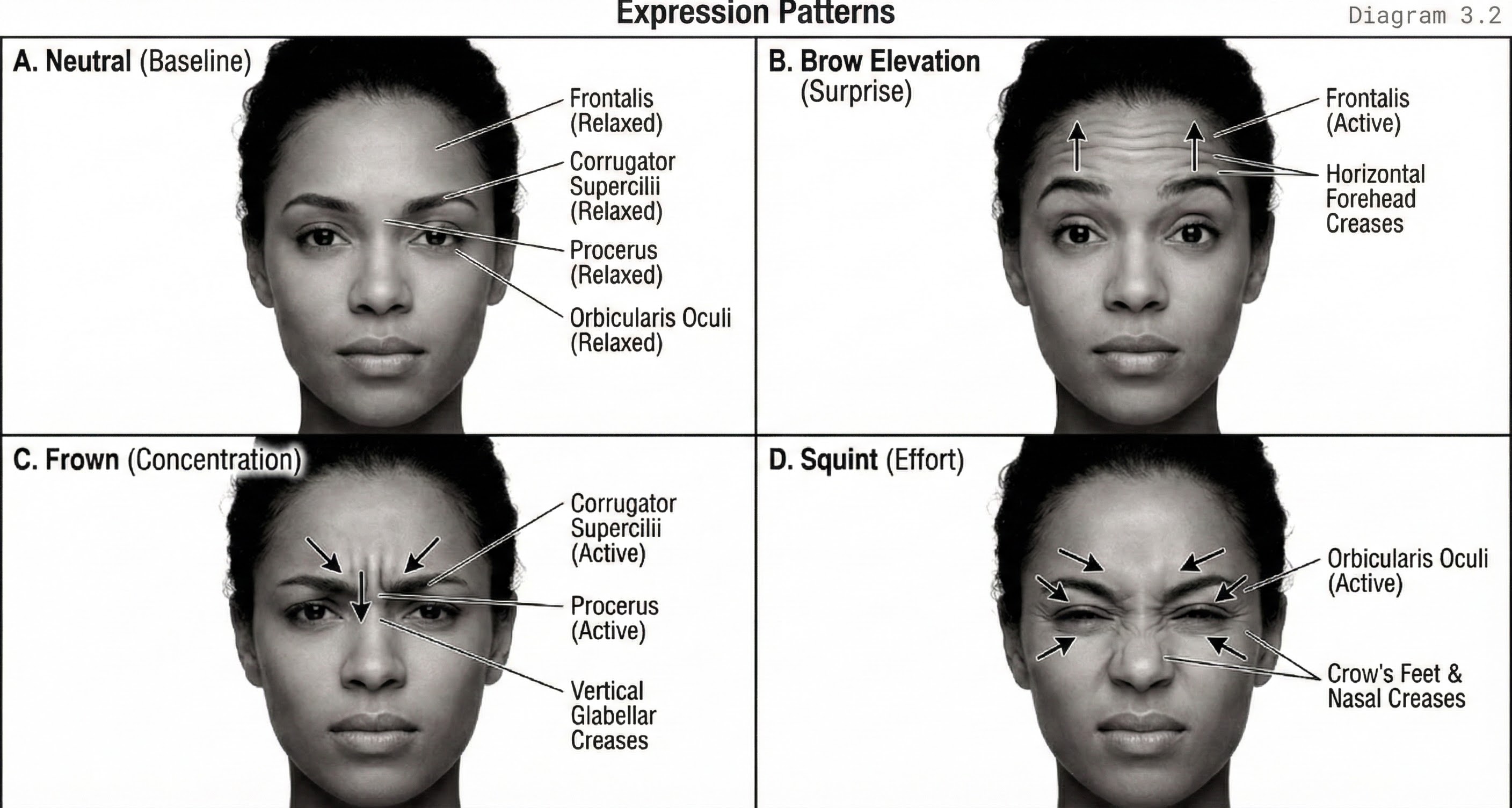

Muscle Interaction Patterns

These muscles interact in complex patterns:

- Brow raising involves frontalis activation with relative relaxation of depressor muscles

- Frowning involves corrugator and procerus activation with frontalis relaxation

- Squinting combines orbicularis activation with varied brow muscle responses

Expression rarely involves single muscle action; rather, patterns of activation and inhibition create expressive outcomes.

Expression Patterns

Purpose: Show brow behaviour across key expressions

A four-panel figure showing a face in neutral, brow elevation (surprise), frown (concentration), and squint (effort). Each panel indicates active muscles with highlighting and shows resulting brow position and crease patterns.

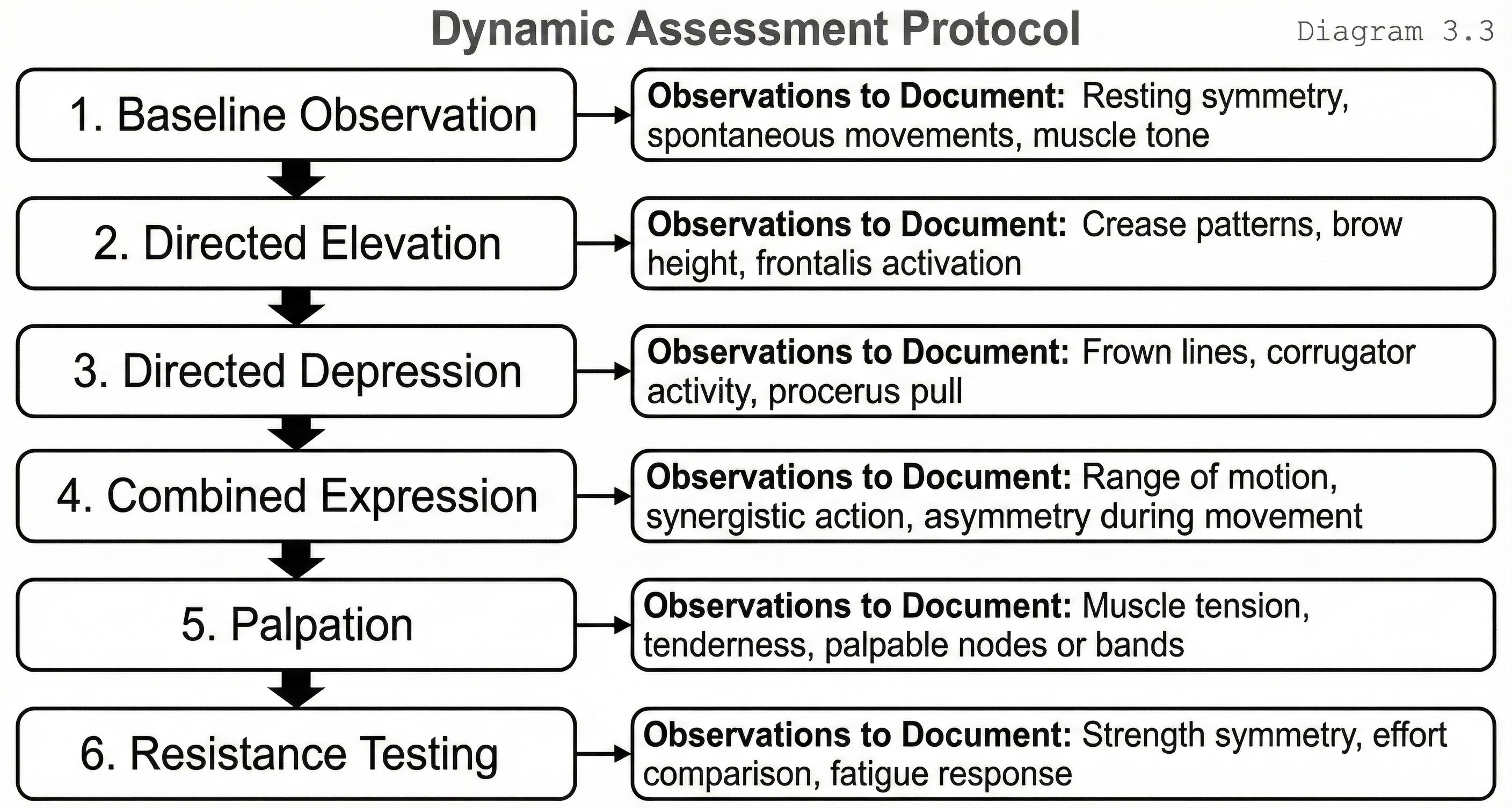

Methodology

Muscle dynamics assessment methodology combines observation, directed activation, and palpation during movement. The protocol examines each relevant muscle both in isolation and in combination with others.

Baseline Observation

Establishes resting muscle tone and brow position. The practitioner observes the client at rest, noting brow height, shape, and any asymmetry. Resting position reflects baseline tone across elevator and depressor muscles. Deviations from expected neutral position suggest muscular factors warranting investigation.

Directed Activation Assessment

Instructs the client to perform specific movements:

- For frontalis assessment: client raises brows as high as possible; observe elevation range, symmetry, and horizontal crease pattern

- For corrugator assessment: client frowns or brings brows together; document medial brow movement, vertical crease formation, and symmetry

Combined Expression Assessment

Evaluates natural expressive patterns. The client is asked to display surprise, concern, confusion, and concentration. These expressions activate muscle combinations in naturalistic patterns. The practitioner observes how the brow responds to these combined activations, noting any asymmetries or unexpected movement patterns.

Palpation During Movement

Provides tactile confirmation of visual observations. The practitioner places fingers on the frontalis during elevation, on the corrugators during frowning, and notes the intensity and distribution of muscle contraction. This confirms which muscles are active and reveals muscle bulk that may not be visible.

Resistance Assessment

Tests muscle strength by asking the client to perform movements against gentle pressure. The practitioner places fingers on the brow and provides resistance while the client attempts to raise or lower. Relative strength of elevator versus depressor function becomes apparent through this assessment.

Dynamic Assessment Protocol

Purpose: Guide systematic muscle dynamics assessment

A flowchart showing the sequence of muscle dynamics assessment. Boxes indicate assessment steps (baseline observation, directed elevation, directed depression, combined expression, palpation, resistance testing) with arrows showing progression.

Techniques

Video Documentation Technique

Captures dynamic behaviour that static photographs cannot represent. The practitioner records the client performing directed movements and natural expressions. Slow-motion playback reveals movement patterns, asymmetries, and timing characteristics. Video documentation provides reference for design decisions and outcome comparison.

Muscle Isolation Technique

Guides clients to activate specific muscles independently. Many clients have limited proprioceptive awareness of facial muscles and initially produce combined movements when asked for isolated activation.

The practitioner provides coaching: "Try to raise your brows without wrinkling your forehead," or "Move only the inner portion of your brow downward." This coaching reveals both muscle function and client's degree of voluntary control.

Functional Assessment Technique

Evaluates how muscle dynamics affect daily activities. The client is asked about common expressions, occupational facial demands, and any concerns about expressive appearance. This contextualises muscle assessment within the client's actual expressive usage patterns.

Botulinum Toxin History Assessment

Documents any previous neuromodulator treatment affecting brow muscles. Prior botulinum toxin treatment alters baseline muscle behaviour and may have created patterns of compensation or asymmetry. The practitioner documents treatment history, areas treated, and any residual effects.

Professional Notes

Muscle dynamics assessment requires patience and skill in directing client behaviour. Many clients feel self-conscious performing exaggerated expressions and need encouragement and normalisation. The practitioner creates an atmosphere where expressive assessment feels clinical rather than performative.

Age-related changes affect muscle dynamics. Frontalis strength may diminish or compensate for upper eyelid heaviness. Repeated corrugator activation over decades may create resting vertical creases. The practitioner considers age-appropriate expectations when interpreting dynamic assessment findings.

Neuromuscular conditions affecting facial muscles require recognition and appropriate referral. The practitioner who observes weakness, asymmetry, or movement abnormalities inconsistent with normal variation should consider whether medical evaluation is indicated. Brow design may be deferred pending clarification of neuromuscular status.

Common Mistakes

Static-Only Assessment: Neglects the dynamic dimension of brow behaviour. The practitioner who designs based solely on resting appearance may produce work that distorts unacceptably during expression. Every brow assessment should include dynamic evaluation.

Failure to Detect Asymmetric Muscle Function: Leads to asymmetric outcomes. Even when resting brow position appears symmetric, underlying muscle strength or activation pattern may be asymmetric. Dynamic assessment reveals these asymmetries.

Overlooking Frontalis Compensation: Misses important diagnostic information. Clients with upper eyelid heaviness or brow ptosis may chronically elevate frontalis to improve vision or appearance. This compensation masks true resting brow position and predicts that relaxation of compensation will lower the brow.

Assuming Consistent Muscle Function Across Contexts: Ignores situational variation. Muscle behaviour during clinical assessment may differ from behaviour during daily activities, emotional stress, or fatigue. The practitioner recognises assessment findings as samples rather than complete representations.

Expert Insights

The master practitioner reads muscle dynamics quickly through trained observation, identifying frontalis strength, corrugator activity patterns, and expressive tendencies within moments of meeting a client. This rapid reading guides subsequent systematic assessment rather than replacing it.

Predicting how design will behave dynamically requires integrating structural and muscular understanding. The brow design that honours both skeletal architecture and muscle dynamics will maintain appropriate appearance across the range of expression. Designs that sacrifice one consideration for the other will exhibit problems in the neglected dimension.

Muscle dynamics findings sometimes indicate that certain design approaches are contraindicated. Very strong corrugator function may preclude certain medial brow designs. Hyperactive frontalis may argue for conservative positioning that will not appear excessive during elevation. The master practitioner uses muscle assessment to identify what will not work as well as what will.

Practical Application

Muscle dynamics assessment occurs during initial consultation following structural assessment. The practitioner positions the client appropriately—typically seated with face at practitioner eye level—and proceeds through the assessment protocol. Findings are documented with notes regarding design implications.

Design proposals incorporate muscle dynamics predictions. The practitioner explains how proposed designs will behave during expression, demonstrating if possible by asking the client to animate while visualising the proposed design on their face. This preview supports realistic expectation formation.

Post-procedure assessment includes dynamic evaluation. The practitioner has the client express during review appointments to assess how the completed work performs dynamically. Any concerns about expressive behaviour are documented and inform approach to future work.